I’m going to tell you about who

I am through two art pieces.

I found these during my art history major in college. They would come to encapsulate two aspects of my identity that I first became aware of when I was 12: one, that racially, I’m many things—Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and German. And two, that I am gay.

LORRAINE RUBIO

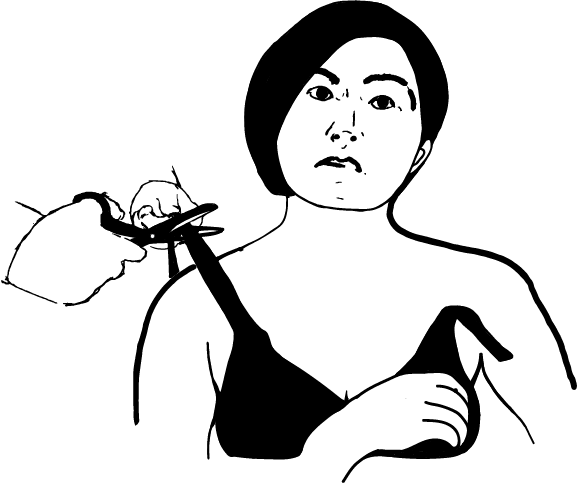

Cut Piece (1964), Yoko Ono

In Cut Piece, Yoko Ono sits silent in her most expensive suit. A pair of scissors is next to her. The audience is invited to come forward and cut off parts of her clothing.

When Ono performed Cut Piece, she was already recognized as an international artist. As a result of this and the fact that Cut Piece relies on audience interpretation of instructions, in each of the theaters the status of her female-ness was determined and performed by the audience.

In New York and London, she was seen resentfully as a feminine totem of Japan—though in 1964 Japan began its re-opening to the world, it wouldn’t normalize US diplomatic relations until 1972.

In Japan, she was divorced from her Japanese-ness: politely interacted with, but not embraced.

As a college senior I fell into Cut Piece. Ono encourages other people to stage her pieces, so I did.

I first became aware of my racial makeup being something that wasn’t ‘normal’ when a kid around the middle school vending machine asked me if I was adopted. I knew what my mom and dad looked like but had never thought the mix of the two would create something totally alien from the two. This confused me, and I wanted and searched for a person in TV and books that I could relate to.

Because I grew up as a military kid—seven moves before 7th grade—I had allowed myself to be adaptable to a fault, allowing my race to be picked and prodded at by anyone who couldn’t easily identify my racial background.

Six months after graduating college with my undergraduate degree in art history, I felt like I was in this place to embody Yoko—to willfully throw myself into space, like a human litmus test. I decided to perform Cut Piece.

But by stepping into the role—metaphorically, throwing myself into the crowd of 30 people at a fringe-y East Village open mic—I caught myself, not allowing myself to be devoured.

When Ono performed Cut Piece, she was already recognized as an international artist. As a result of this and the fact that Cut Piece relies on audience interpretation of instructions, in each of the theaters the status of her female-ness was determined and performed by the audience.

In New York and London, she was seen resentfully as a feminine totem of Japan—though in 1964 Japan began its re-opening to the world, it wouldn’t normalize US diplomatic relations until 1972.

In Japan, she was divorced from her Japanese-ness: politely interacted with, but not embraced.

As a college senior I fell into Cut Piece. Ono encourages other people to stage her pieces, so I did.

I first became aware of my racial makeup being something that wasn’t ‘normal’ when a kid around the middle school vending machine asked me if I was adopted. I knew what my mom and dad looked like but had never thought the mix of the two would create something totally alien from the two. This confused me, and I wanted and searched for a person in TV and books that I could relate to.

Because I grew up as a military kid—seven moves before 7th grade—I had allowed myself to be adaptable to a fault, allowing my race to be picked and prodded at by anyone who couldn’t easily identify my racial background.

Six months after graduating college with my undergraduate degree in art history, I felt like I was in this place to embody Yoko—to willfully throw myself into space, like a human litmus test. I decided to perform Cut Piece.

But by stepping into the role—metaphorically, throwing myself into the crowd of 30 people at a fringe-y East Village open mic—I caught myself, not allowing myself to be devoured.

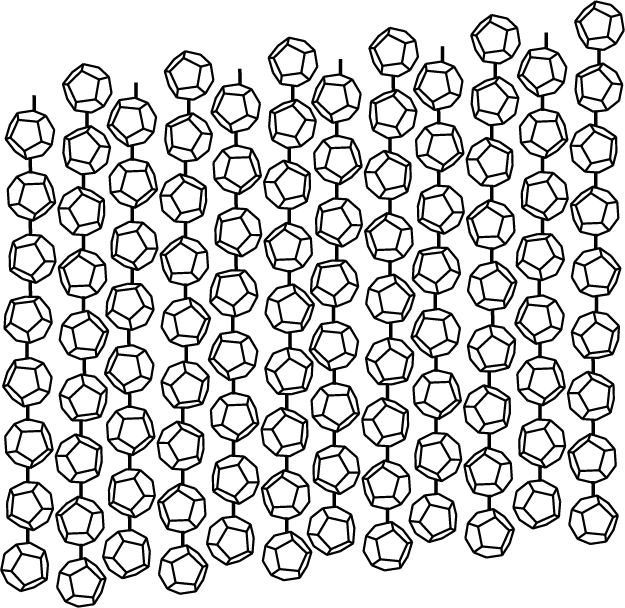

Beaded Curtains (1989-95), Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Felix Gonzalez-Torres evaded being labeled ‘gay artist’ or being attached to his Cuban heritage. Given the fact that he worked in the 1980s and ‘90s, creating work centering on his experience of the AIDs crisis, it would be very easy to do just that: politicize his identity.

I read his work as a deep memorial of life and love lost told through domestic objecthood. In Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the Guggenheim and David Zwirner hangs beaded curtains in seven colors, each color represents a stage of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ partner Ross Laycock passing. I walked through heavy beaded curtains and could feel the weight of their relationship, of Ross.

Gonzalez-Torres claimed that though most works blocked or changed public space, they were always meant for an audience of one. I fell in love with the way Felix loved Ross. I love this depiction of love, because it goes past the glamorized exterior of a gay life and celebrates the tender and human aspects of partnership. An unabashed romantic, as a college junior, I wanted to see a partner the way Felix did.

Twist

After college and after performing Cut Piece, I worked as both an art journalist and marketer. I navigated conversations and challenges working towards a personal mission of creating greater recognition of artists of hybrid identity, such as Yoko Ono and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Towards the end of this time I applied and was accepted to an MBA program in New York.

Having finished my MBA, I’m no longer pursuing art. The world and my view of it has changed since opening myself to the world outside the art world. Just as the world’s reaction towards Yoko Ono has shifted to one of celebration, there’s a slow but increasing rise in the women of color seen in broader culture.

We’re far from done though.

At an LGBTQ-focused company reception in the fall of my second year of the MBA, I was standing in a circle with all queer women and we all discovered that we had come to business school from what business school admission committees call “non-traditional” backgrounds: historians, teachers, producers in art, film, and education. We had all felt that as queer women we could create the largest impact through making the fringes bigger—versus expanding mainstream norms of leadership.

For decades the LGBTQ community has done the hard lift to elevate itself and other communities. I think it’s time to push the edges—from the middle of the pie, not the fringes.

Lorraine Rubio recently graduated from the MBA program at NYU Stern.

Before that she worked as an arts journalist and marketer.

@lorrainerubio

Before that she worked as an arts journalist and marketer.

@lorrainerubio

︎ READ RANDOM